February 18, 2009

By JOSHUA BROCKMAN

You thought your retirement plan was being managed by smart advisers in the most conservative way.

You thought the mix of stocks and bonds was appropriate.

You thought your nest egg money was secure.

Think again.

A new study, U.S. Pension Reform: Lessons From Other Countries, commissioned by the Ford Foundation to look at how U.S. pension funds stack up to their counterparts overseas reveals that the equity weighting — or the percentage of a funds’ monies devoted to stocks — is much higher in American funds. That means your nest egg is more fragile than you imagined.

The problem, says the study’s co-author Jacob Kirkegaard, a research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, is that “the risk appetite of these plans has been going up in the last couple of decades, despite the fact that we know that the average age of people in these plans went up.”

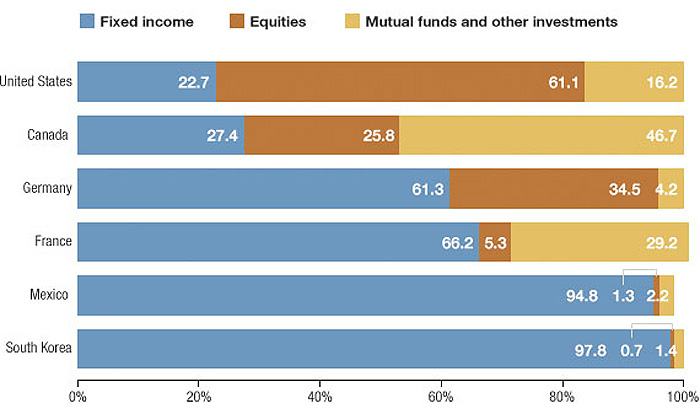

According to the study’s examination of several countries, U.S. pension funds had one of the lowest percentages of bond or fixed income investments (22.7 percent) and the highest percentage of stocks (61.1 percent). Germany, which had the second highest percentage of stocks (34.5 percent), still had 61.3 percent of its pension assets invested in bonds and other fixed-income assets, which are widely considered to be more conservative investments. Many countries have regulations in place that require them to be more conservative with pension investments, says Kirkegaard, adding that these rules have tightened as populations have aged.

When the economy is buzzing along, the upside to stocks is clear — they typically offer the promise of greater returns. Bonds usually have more modest returns, but they provide stability and security. A case in point is U.S. treasuries, which are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

But stocks have taken a beating in this recession — the Dow was down more than 43 percent since the end of 2007 — and so has your nest egg if you had substantial exposure to equities in your retirement accounts at the start of the downturn. Instead of reaping the benefits of upwardly moving stock prices, companies and state and local governments have had to contribute a lot more money to their traditional, defined-benefit pension funds just as the economy has shifted into crisis mode.

For years, pension experts have said that the target population covered by any pension plan should dictate how a portfolio is managed, says Olivia Mitchell, executive director of the Pension Research Council at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. That means that the older the employee and retiree base, the more conservative a plan should be.

“Many plan sponsors hoped that by investing in the stock market they would make higher-than-expected returns, thereby reducing the need to contribute so much,” she says. And that happened in the 1980s and 1990s. But it didn’t last.

“There is a downside to volatility and we’re now experiencing it with a vengeance,” she says.

So what will happen?

Kirkegaard says the pressure on companies to increase contributions will most likely lead companies to lay off more people than they otherwise would have.

The good news for workers with corporate defined-benefit plans is that their plans are partially insured by the federal government through the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. In 2008, there were 44 million Americans who were either actively working or retired with a private sector defined-benefit pension plan from a company, according to the PBGC. These plans pay out a fixed amount of money each month until you die.

But no such protections exist for the roughly 20 million state and government workers or for average investors with 401(k) or IRA plans.

The study also found that some state and local government pension funds are drastically underfunded — a crisis that looms large because they support some of the oldest work forces in the nation. A case in point is the Indian State Teachers Retirement Fund, which had a funding ratio of 43.4 percent in 2006, or the Illinois State Employees Retirement System, which had a funding radio of 52.2 percent for the same year. Ideally, this figure should be closer to 100 percent, Kirkegaard says.

An individual retirement account or 401(k) retirement plan differs in that it is a defined-contribution plan, which means that you, as an individual, can determine how much money you contribute. In 2007, 46.2 million households owned some type of IRA, according to the Investment Company Institute, a mutual fund industry trade group. And 48.5 million workers in the U.S. were active participants in a 401(k) plan in 2007, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

Most Americans rely on Social Security payments to support them in their retirement years. But it’s usually not enough. And many people can’t afford to open 401(k) or IRA accounts if they’re living paycheck to paycheck.

“When such a large share of Americans have no private savings, they have no benefit of a 401(k) or an IRA system,” Kirkegaard says. The people who benefit the most from these retirement plans are the well-off, he adds, since those who pay little or no taxes derive no benefit from the tax breaks these plans afford.

In Depth

Listen To One Of The Co-Authors Discuss The Study

© NPR