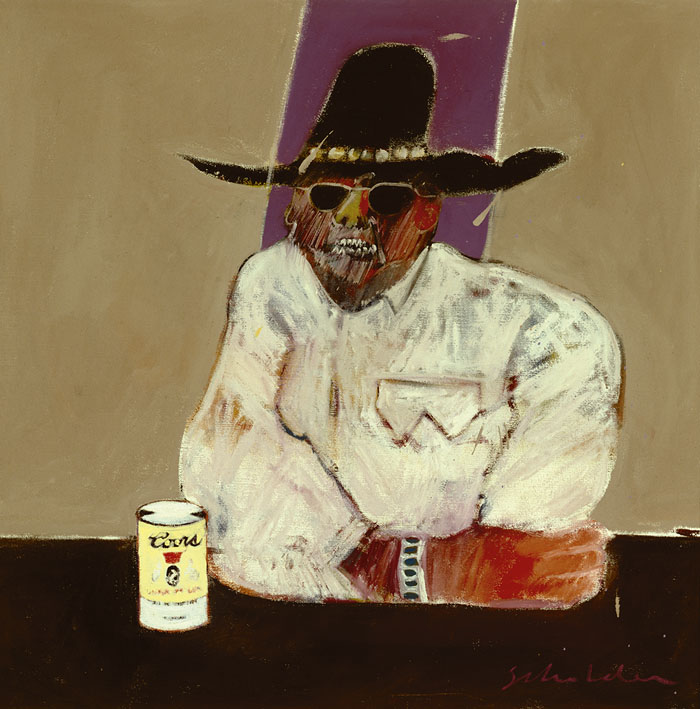

Indian With Beer Can (1969) is one of Fritz Scholder’s most haunting images from his “Indian” series. Scholder painted what he observed, including alcoholism in Indian Country. Bill McLemore/Collection of Ralph and Ricky Lauren.

December 24, 2008

By JOSHUA BROCKMAN

Fritz Scholder broke almost every rule there was for an American Indian artist. He combined pop art with abstract expressionism. He shunned the sentimental portrayal of traditional Indians and in so doing helped pave the way for artists who followed.

Scholder was only part American Indian, and when he created the work that put him on the art world map — his “Indian” series in the 1960s — he made a lot of people mad. The first painting had the word “Indian” stenciled on it, as if the image couldn’t be identified without the label.

Now, Scholder is the subject of three exhibitions across the country. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian has organized two — one in New York and one in Washington, D.C. — both called “Fritz Scholder: Indian/Not Indian.” And in Santa Fe, N.M., where Scholder taught in the 1960s, the Institute of American Indian Arts Museum has organized an exhibition titled “Fritz Scholder: An Intimate Look.”

Painting Contemporary Reality

Another iconic image from Scholder’s Indian series is Indian With Beer Can (1969).

“It’s still haunting; it’s still devastating seeing these white teeth, a distorted face to suggest a skull,” says exhibition co-curator Paul Chaat Smith, who works at the National Museum of the American Indian. “You can’t see the figure’s eyes, they’re behind sunglasses — incredibly arresting and powerful work even today, but back then it was extraordinary.”

The can of Coors in the foreground is a vivid example of how Scholder painted what he observed. And that included alcoholism in Indian Country.

“He’s really talking about the condition of the American Indian that he saw,” says “Indian/Not Indian” co-curator Truman Lowe, a contemporary-art specialist at the National Museum of the American Indian. “And it’s not pretty.”

But it’s not always ugly. Standing in one of the galleries at the museum in Washington, Scholder’s second wife, Romona Scholder, points to a well-known 1971 painting called Super Indian No. 2.

“We were at Santo Domingo Pueblo, and we had kind of left the crowd and walked around a corner, and here sat a buffalo dancer,” she recalls.

Scholder went home to paint him. In the portrait, the dancer wears a horned headdress and beads around his neck. And in his hand — just as Scholder saw him — instead of the traditional rattle, there’s an ice cream cone with two scoops.

“He went, ‘Oh my God,'” says Romona Scholder, recalling her late husband’s reaction to the incongruous sight. “And I think that that’s why this painting is quintessentially Scholder — because he picked up [on] that Indian-as-mythical-being and Indian-as-ice-cream-cone-eater.”

In the 1982 PBS documentary Fritz Scholder: An American Portrait, the artist discussed the origins of the “Indian” series.

“I succumbed to a subject that I vowed I would never paint: the American Indian,” Scholder said. “The subject was loaded, but here I was in Santa Fe. It was hard not to be seduced by the Indian.”

Origins Of A Colorist

Scholder was one-quarter Luiseno, but he said he grew up “non-Indian.” Born in 1937 in Breckenridge, Minn., he spent his childhood in North Dakota and South Dakota. In Pierre, S.D., he studied with his first American Indian instructor, Oscar Howe. When he moved to California in the 1950s, he studied with the celebrated pop artist Wayne Thiebaud.

In the documentary, Scholder likened himself to the abstract expressionists: “The thing is to get the paint on the canvas. I don’t care if you use your fingers, your rag, brushes, cardboard — it doesn’t matter — it’s getting that paint on the canvas. You get it on the canvas and you see what happens. It drips, it smears, it’s thick or it’s thin or you make washes. I consider myself a colorist. One color by itself isn’t that interesting — it’s the second color and a third color, and a dialogue starts and pretty soon you’re swept up in it. You really don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

Scholder shared his enthusiasm for painting with students at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. In 1964, he accepted a teaching position there and remained on the faculty through 1969. It was during this period that his career skyrocketed.

Even though he was shy, he didn’t hesitate to put himself in the center of his canvasses. Romona Scholder points to some paintings from the Human in Nature, Monster Love and American Portrait series on display in the Washington exhibit.

“All of these paintings are self-portraits of some aspect of himself,” she says. “He himself influenced the shape of the paintings, the shape of the people. He had some scoliosis in his back, and one shoulder was up a little higher than the other, and it shows up in all of his paintings.”

Scholder’s work was largely autobiographical, and it often featured iconic and dyadic figures. The artist had scoliosis and so his right shoulder was slightly higher, an anatomical feature that is on display in Portrait with White Suit (1983). Collection of the Albuquerque Museum.

Indeed, the right shoulder is more pronounced in a series from the 1980s, including the painting Portrait With White Suit (1983), where an asymmetrical figure is set against a lavender landscape.

Destination: New York City

It was in the 1980s that Scholder went to New York as part of his mission to make it, to become a star. Andy Warhol painted his portrait. He went to openings and was embraced by an art world intrigued by his otherness.

At the Smithsonian’s galleries in lower Manhattan, the emphasis is on paintings and sculpture Scholder created from the 1980s until his death in 2005. The series on display here, including Mystery Woman, Possession and Shaman, aren’t just about himself. They’re also inspired by the esoteric objects he collected.

Living With His Possessions

Another Possession is a winged sculpture of a demon with a skull-like head; it was once perched at the edge of Scholder’s pool at the adobe-walled compound, filled with palm trees and oleander, where he lived in Scottsdale, Ariz.

It echoes the Egyptian sarcophagus, the mummies and skulls that are part of the collection of artifacts that he lived with and used as props or springboards for his art.

“All of these things give you the impression of incompatibility,” says Renaissance professor Bob Bjork, who was Scholder’s friend and shared an interest in old books. “But what’s amazing is that they meld into a perfect work of art — it’s as if you’re entering a painting. He had an amazing ability to juxtapose objects and make them work together in an incredible way.”

Scholder also lived with thousands of books, some of which he created.

Bjork, the director of the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, remembers a poem about Sept. 11, 2001 from Scholder’s illustrated From the Cave:

Fun left that morning.

We witnessed the fall

in real time.

Birds were burning.

Time to paint flowers.

That year, Scholder’s art took an even more personal turn. His widow, Lisa Markgraf Scholder, says he had been battling diabetes for years.

“This was a time of illness being taken very seriously and lots of blood work,” she says. “And in between blood tests, Fritz would always connive his doctors into giving him extra vials so that he might take them home and experiment.”

That led to Blood Skulls, a series of skull images on motel stationary fashioned using his own blood and Diet Coke.

Scholder’s Afterlife

In his last self-portrait, crafted in 2003 and on display in New York, the artist sits in his studio, leaning on a cane with an oxygen tube in his nose. A large pool of blood encroaches from the foreground. A gray Egyptian cat stares up at him; in the center of the floor are a book and a photograph.

Scholder would likely smile at the questions his works still provoke today. His creations have an afterlife that curator Lowe says resonates with both Indians and non-Indians.

“He was an instrumental part of breaking down the stereotype of Indian painting and actually changing it,” Lowe says, “so that, in a real sense, it’s freeing up the succeeding generations of artists to work in whatever medium and in whatever subject matter and whatever direction they choose.”

In 1975, Scholder did a series of etchings called Ten Indians. Each portrays a different member of a tribe dressed in regalia. The last one is a Luiseno. It’s Scholder — in sunglasses and an ascot.

The Smithsonian exhibition poses the question: Indian or not Indian? Fritz Scholder remained both, right until the end.

More On Scholder

© NPR